A tight knit and brutally honest essay on familial conflicts and the complications of living a Western dream in an environment of limited possibilities.

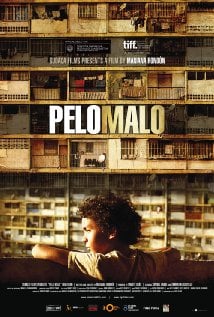

Nine year old Junior is on the war path with his mother. What else is new? The ageless story of kid versus parent is told again, this time in the tough streets of the projects in Caracas, Venezuela. His mother, Marta, has lost her job and is in the process of giving up every shred of self-respect she has to get it back. Since her husband died she has no money, no skills and two children to look after. She is living from day to day. And then, there’s the hair.

Nine year old Junior is on the war path with his mother. What else is new? The ageless story of kid versus parent is told again, this time in the tough streets of the projects in Caracas, Venezuela. His mother, Marta, has lost her job and is in the process of giving up every shred of self-respect she has to get it back. Since her husband died she has no money, no skills and two children to look after. She is living from day to day. And then, there’s the hair.

Junior (Samuel Lange Zambrano) is very concerned about his hair. He is every bit as concerned about his hair as his mom Marta (Samantha Castillo) is concerned about how they will eat. As this conflict plays out in the screenplay, the bonds of love between the two are tested.

In between the two is Carmen (Nelly Ramos), the mother of Junior’s deceased father. To Marta, her mother-in-law is a drop in day-care service with the extra added fee of having to listen to her advice. Beneath Carmen’s demeanor is a barley hidden disapproval of Marta’s abilities as a mother. Beyond that, Carmen has a mysterious take on Junior’s dream of becoming a rock star and wants Marta to give him to her to raise. Carmen goes along with the fantasy for some reason that is murky, at best. She makes him a stage costume, which he rejects because it looks girlish.

Meanwhile, the film follows Junior and his friend (María Emilia Sulbarán) through the streets and projects of Caracas, poking their heads into every curious place and event that presents itself. Their capsule descriptions give us a fascinating look at the big city, with the unabashed honesty only a child can summon. Streets gangs beckon to Junior, but he is not interested. The gangs, like his grand-mother, are not so much threatening as they are simply available. There is slowness to life in the tenements, but as there is slowness, there is an assurance about how things go. Nobody feels the necessity of explaining anything to Junior, they are confident he will find out on his own.

Tensions pull every which way in Mariana Rondón’s neo-realist coming of age story. There is no beginning or end, nor are there any spectacular breakthroughs or enlightenments. There is day after day of the struggle, the dreams, the hunger and the fear of fading away. There is also the need for acknowledgement, the yearning for the recognition of one’s existence and one’s humanity. Too many people and not enough possibilities, but, still, the strong survive.

The reason they survive is because they care about each other and acknowledge each other. The real world is a construct that is best left to itself. In the end, reality is what loved ones say it is, not what is promised by the media.

Thoroughly honest production values make this an entertaining film to watch, although it would have been better if it contained a more distinct political or familial statement. The slowness of the movie is aggravated by the fact that it is so completely honest. We have all been there before. So we wait for something new and different, but it never comes. In the end, the film gets an A+ for honesty and realism, but a C- for entertainment.

Having said that, the two lead performances by Zambrano and Castillo are perfect, as are the supporting performances by Ramos and Sulbarán. The characters of Junior and his friend (Sulbarán—credited only as “La Nina”) are so engrossing that the film begs for another feature featuring only them. When they stand on the balcony of their project apartment and comment on the vast variety of tenants in the adjacent building it is like a trip to another world.