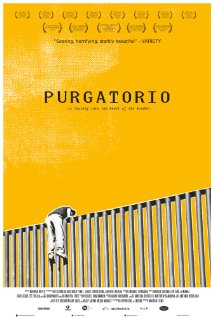

A scary and stirring reporting of the reality of life on the Mexican / US border.

Rodrigo Reyes simmering treatise on the human condition in the worst of all worlds starts from the beginning. Children laugh and play, full of good intentions and dreams of the future. But something happens to them when they grow. They lose their common language and they grow apart. “A line on paper means nothing, but a line in the sand means everything.” For thousands, maybe millions, of Mexicans every year, it means life or death.

Rodrigo Reyes simmering treatise on the human condition in the worst of all worlds starts from the beginning. Children laugh and play, full of good intentions and dreams of the future. But something happens to them when they grow. They lose their common language and they grow apart. “A line on paper means nothing, but a line in the sand means everything.” For thousands, maybe millions, of Mexicans every year, it means life or death.

The scene shifts to an interview with a thirty year drug addict, then to the stark blue sky, the desert and two men waiting for their chance to climb the fence and risk their lives to work in the USA. Death is a distinct possibility and being caught and sent back is a probability. “Without work there is nothing,” they say. The climb over the twenty foot tall wall of vertical iron pipe, supposedly difficult or impossible to scale, takes the 26 year old about sixty seconds. But that is not the hardest part.

Director/writer Reyes (co-written with Hugo Perez) looks at the present, and into the past, for clues as to how a line in the sand has been transformed into purgatory. For some the line means death, but for most it means a never ending cycle of suffering, humiliation and familial desperation. The final insult is there is no choice but to do it all over again. A junk tire rolls across the packed sunbaked dust of a border town. Cut to mountains of worn out rubber tires, waiting to be joined by the walking dead around them.

Shifting back and both between interviews with those caught up in the angles and corners of border survival, the screen fills with the artifacts of the purgatory in which they live. Junk yards filled with burned out cars and official looking vehicles burned to black hulks by a drug deal spun out of control. Wire fences along the border plastered with streaming plastic detritus torn apart by a wind that never seems to let up. The soundtrack of the wind, highway traffic and footfalls through a faceless desert to a nameless future are all the sounds we hear. Occasionally, there is no background sound at all, as when we listen to the coroner or see the children’s cemetery.

A US citizen patrols the area, a volunteer, on his own, with a self-described “Samaritan” t-shirt. He is picking up scraps of trash that he believes to be trail markers, making it harder for illegals to find their way. A Mexican official speaks in positive tones about how things will be better. The woman on the street grieves over the loss of her son at the hands of a drug gang. As she describes the fathomless depth of corruption that bedevils law enforcement officials, a police funeral ends with a shotgun salute as the scene cuts to children laughing and describing their favorite guns. “Bam-bam,” “ratta-tat-tat,” they yell. “The AK-47 is best, they are all dead at once!”

Day and night are the same. Day is the silence of the sand and sagebrush with the faint chirping of small birds in the background. Night is the silence of a moonscape of city lights, glaring vehicle headlights crisscrossing the desert and the highway interchangeably and the red lights of the police as they capture illegals for the return trip or wrap the dead in body bags. The soundtrack is almost silent, with nothing but the faint hum of a tow-truck winch preparing to take the car on its last trip.

Civilizations are what they leave behind, not what they thought they enjoyed. In another nod to Patrick Keiller’s “Robinson in Ruins,” cut to the buried silence of the Titan Missile museum with its corpses of the cold war standing in eternal, emasculated vigilance, each in its own silent sarcophagus. Work or die. A newspaper man is interviewed, saying it is all he can do to try to be objective, as the presses stand idle in the background. “Crime is news,” he says, and then breaks down into a laughter that is thinly controlled hysteria.

20,000 dogs euthanized per year against the backdrop as silent as death, filled later by the hum of the burners in the furnace. At one shelter, a woman admits, “My biggest fear is going to hell.”