Lacking in originality and nearly devoid of sunlight, this elegant psychological study is nine parts caution for every one part closure.

Lacking in originality and nearly devoid of sunlight, this elegant psychological study is nine parts caution for every one part closure.

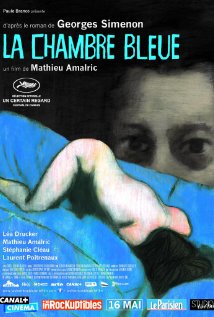

Directed and written by Mathieu Amalric (co-written by leading lady Stéphanie Cléau), “The Blue Room” is superficially a cautionary tale about marital infidelity and, on a deeper level, a psychological study in promises made, and implied. Based on Georges Simenon’s classic novel of the same name, the film tells the story of adulterous lovers Julien (Amalric) and Esther (Stéphanie Cléau) who meet in the “blue room” of a French Hotel no-tell to have most delicious and forbidden sex.

Amalric shows himself to be a master at telling the story, in gorgeously muted tones, of the sweet nothings that transpire in the afterglow of seething copulation. In this story, Esther’s passion exceeds Julien’s, as displayed by his guilt and mixed emotions about their sumptuous romps in the verdant and fertile French countryside. His faithful wife Delphine (Léa Drucker) and daughter Susan await him at home. Esther’s life is nothing but a mediocre marriage that has been reduced to a death watch over her terminally ill husband Nicolas. Her mother later claims that Nicolas, Julien’s classmate, only proposed to Esther for the family’s money from the start. Her reflection of Julien’s guilt is her conviction that they were made for each other from their birth to the present and any other connections were made to be broken.

Blood is spilled during the excitement of the coupling and blood is the symbol of promise. To Esther, this is a blood oath. To Julien, it is a problem to be dealt with. “Will your wife ask questions?” Esther asks. “I will tell her I bumped into something,” Julien responds, seemingly half asleep. The next drop of blood falls as he reunites with his wife and daughter. This is a blood oath that will not fade away.

Nicolas dies and the autopsy casts doubt on natural causes. Julien’s wife Delphine is poisoned by a mysteriously mailed package. Through a series of intricate flashbacks and police questionings Esther and Julien end up in the same court answering to charges of murder. The verdict decides the question of their allegiance forever. Although this leads to high drama, it also leads to substantial (perhaps intentional) confusion about who is being tried for what; each for their spouses’ deaths, each for the other’s spouse’s death, or both for both deaths. The vagueness of the proceedings stumps the audience, but echoes, with clarion resolution, the ill-fated and poorly considered dreams of the adulterers.

This is a simple story and there can be no blame assigned to Amalric for the film’s lean 76 minute run time. The story is short and he tells it honestly and directly. Half of the film is narrative recounted by Julien and half is flashbacks to Julien’s immediate past that patch together the deeply flawed love affair. As the puzzle comes together, we see that Esther has known the truth all along. The emotionally crippled Julien puts it together only with glacial tedium, in a fog of leaden bewilderment.

Grégoire Hetzel’s score begins with luscious, though carnally serious, strings. As the story unfolds and the worlds of the two lovers collapse around them the soundtrack becomes increasingly percussive and demanding, flowing smoothly into the final scenes that might as well be the couple taking the final steps to the guillotine. Throughout the film the music is sparse as the film makers allow the two leads to tell the story of their own ill-fated prurience. The testimony is interspersed with questions, prompting and accusations by the interrogating gendarme. This allows Amalric the most scintillating back and forth between Julien’s ill-conceived fantasies and the harsh judgments of the outside world.

In the end Amalric and Cléau shift away from direct blame, as the tone of the plot becomes more a witch hunt with subsequent burning at the stake rather than a fair hearing by one’s peers. In stark contrast to the dreaminess of the opening scenes, and the enduring love in even in the eyes of the betrayed Delphine, here is damnation flowing from the screen.

A well told story, but, after all, one that is lacking in originality and nearly devoid of sunlight, being nine parts caution for every one part closure. The flashbacks are interesting but at times threaten to become an IQ test for the audience where not enough information is provided to make an easy connection between the other tight, sparse and fragmented episode seen ten minutes previous. Nonetheless, first rate production values and a frighteningly sincere voice make film something special.