The second chapter of Disney Gallery: Star Wars: The Mandalorian seems to begin like a weary lap dance for George Lucas, but ends in a brain-rewiring EMP bomb for even the hardcoriest of hardcore Star Wars fans.

While its first few moments spotlight Lucas in a dog-eared, corporate line-towing fashion, viewers should hang in there for the episode to slowly pivot into some fascinating discussion about the humanistic and classical themes of the original Star Wars trilogy.

It’s deep, kids.

These glimpses of traditional “making of” footage are worth the watch for Mandalorian fans and anyone interested in visual storytelling. However, it’s the interviews past the halfway mark which will leave you wishing for a three-hour, special edition cut of “Legacy.”

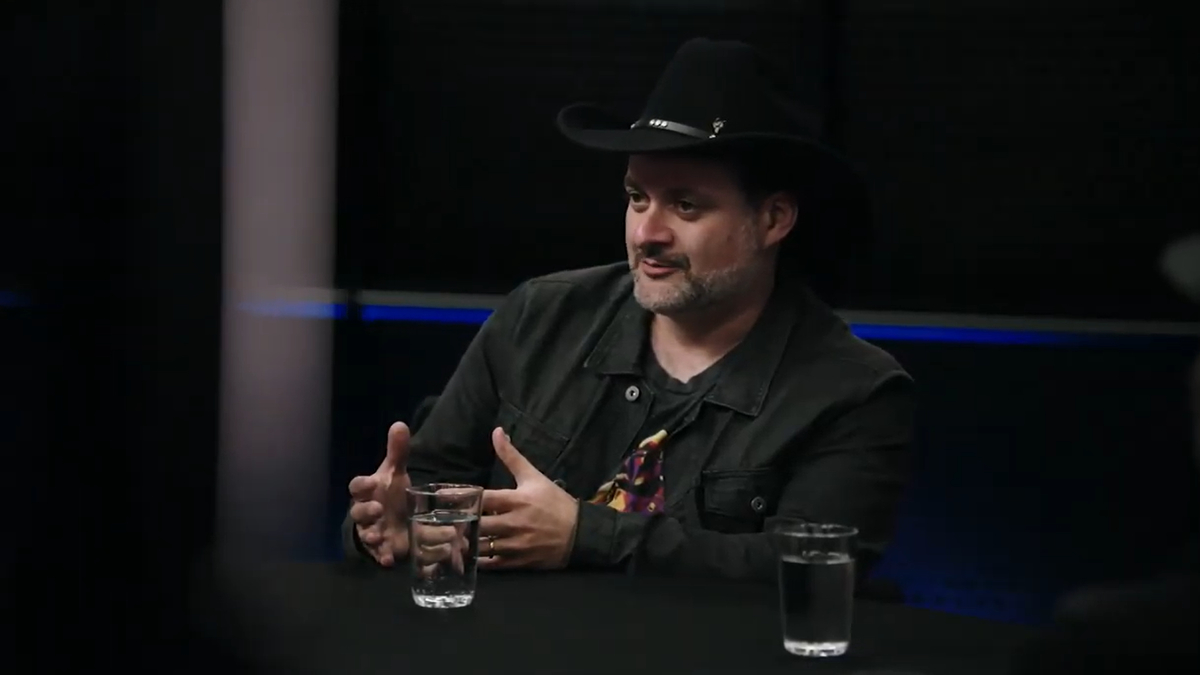

Even more significantly — and perhaps accidentally — the episode positions executive producer Dave Filoni as the beating heart of The Mandalorian.

In “Legacy,” several Lucasfilm powerbrokers are present for a roundtable discussion with input from the four other directors chosen to link together the arc of Season 1.

They all have Thoughts, some more compelling than others. Still, it’s Filoni who holds the floor with a series of impassioned monologues which culminate in a tour de force impromptu speech about what Star Wars is, what it isn’t, and, implicitly, what it never should be.

It’s just a dude in a cowboy hat, talking. But it’s some of the most compelling Star Wars content to unspool from Lucasfilm since the final scenes of Return of the Jedi.

Mind, this isn’t 29 minutes of “I’m Dave Filoni. Welcome to my Ted Talk about the philosophical guts of Star Wars.” Episode 2 also brings in FX crew members, the first Disney Gallery sighting of Pedro Pascal without a helmet, and the perfectly cast Carl Weathers, who plays Mando’s fellow bounty hunter.

Pascal charmingly describes a childhood memory of seeing a single blue lightsaber blade on a distinctive Return of the Jedi poster. The wonder still lighting his face is a show-don’t-tell masterclass; the audience is reminded that yesterday’s kids with the action figures are today’s driving force of new Star Wars material.

Moments such as this, along with such absolute gifts as the original, pre-mega-“improved” footage of the Death Star exploding at the end of A New Hope, serve as reminders that The Mandalorian has wisely and truly anchored itself in the fable qualities of the original trilogy.

It’s telling that the Lucas-focused section opens with long-hold, iconic images from the original trilogy which were wisely carried over into The Mandalorian — stormtrooper helmets, bounty in carbonite. It’s also telling that the prequels are mentioned mostly in passing.

And it’s incredibly telling that the sequel trilogy is mentioned barely at all. Its as if The Mandalorian is, in fact, the true heir to the closing credits of Return of the Jedi, and not The Adventures of Very Angry, Unshowered Luke.

No, this episode knows what brought the commas and zeros to the party. That is the mythic gravity pull and superior storytelling of the original trilogy.

Where the prequels are discussed, it’s in context of Vader’s fate, and also points out the children who grew up with the original trilogy are now in their third generation of films. The children who grew up on the prequels are getting to be parents themselves.

There’s a whole swath of the fandom which views the prequels not with contempt, but Snuggie-style nostalgia. Mentioning this indicates a realization that Star Wars is now old enough and wide enough to have an emotional foothold across several generations, and that handling any output bearing the title is akin to designing a monument for the Washington Mall.

Those most involved with The Mandalorian seem to recognize this.

Many Star Wars fans, while eager to learn what this Boba Fett-type dude was up to, warily approached The Mandalorian, and some early adapters expressed surprise that they liked it so much.

This wasn’t necessarily due to legacy fan disappointment in the sequel trilogy or lingering resentment over the prequels and infamous Special Editions — they were also balking over the guiding presence of Jon Favreau, whose longtime political activism hoisted a red flag.

Was this gearing up as nine episodes of PowerPoint about potential global warming on Hoth?

Favreau is savvy enough to comprehend that where IPs this culturally weighty are concerned, the vast majority of the audience won’t stomach a handheld mirror reflecting the creator’s politics, no matter which side of the aisle they inhabit.

The reason why the original trilogy stands as our modern Greek myths four decades later is that its themes and subject matter are timeless; they transcend race, culture, nation, language, and creed. They transcend time itself. There is a distinct lack of oil crisis and Watergate zingers in A New Hope. Thus, it resounds as loudly and clearly in 2020 as it did in 1977.

Either Favreau came into the project with this understanding, carried over from his resounding success with Iron Man, or Filoni and his co-creators quietly steered a poisonous cable news stream from a blinkered political vision for The Mandalorian.

In any case, five-minutes-ago references from The Daily Show are blessedly missing; Favreau and team acknowledge that these don’t belong in Star Wars, and certainly not in the last bare thread connecting the saga to an exhausted, saturated fanbase.

The benefit of Filoni’s presence shouldn’t be a surprise; the other universally approved modern Star Wars incarnation, The Clone Wars, is partially his baby.

These triumphs prove that it is indeed possible to carry the immense expectations of the Star Wars brand into new material. And Filioni’s humble realization of this is what makes it possible.

Discussions in the latter half of this episode spotlight Filoni’s appreciation of Star Wars as a story which takes place not in a red state or a blue state, but in a galaxy far far away.

Filoni seems to grasp that Twitter is a hellsite where reasoned conversation goes to die in a flaming dumpster. Although he has an account, judging by what he chooses to share and retweet, Filoni has apparently made the conscious decision to remain focused on his keen ability to visually unspool a small story about larger things.

He has not embraced as his mission in life the need to tell others what he thinks about fracking and Supreme Court vacancies via the vehicle of AT-ST combat and nanny droids.

Filoni’s comments — too good and too extensive to fully transcribe here — are instructive and thoughtful, not only as a writer and storyteller but as a genuine Star Wars fan.

He and Favreau discuss The Mandalorian as a Western and touch on the character journey of IG, the droid who serves as Mando’s mechanical foil.

Filoni shares his understanding that successful stories from this universe are about much more than cutesy puppets. They provide insight “about humanity using non-human characters.”

Just so. While this episode also brings the importance of good FX into focus and spends some time focusing on computer animation as art, not merely a conveyor of explosions and dinosaurs, we see more about why The Mandalorian succeeds where the sequels fail.

This is about a man seeking redemption and his exploration of the role of father.

“It’s not all the things we dress Star Wars in,” Filoni points out. He perceives, correctly, that these are not films about space wizards and laser-blasting spaceships. They are a medium through which we pass on the importance of the upending of evil with persistent goodness.

This understanding was largely what was missing from the fractured sequels, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the prequels.

Whatever emotional substance their stories contain are provided by the original trilogy. Filoni points out, “the son saves the father, the father saves the son. That’s the story of Star Wars.”

And it is also the story of The Mandalorian, but the series doesn’t feel like a soft reboot. It feels like a sweeping adventure tale with something universally human to say, with cute moments and funny moments and fanservice moments but, mostly, meaningful moments.

Filoni expands on his understanding of the original trilogy as essentially a story of father-son atonement by noting that Obi-Wan Kenobi functions as Anakin Skywalker’s brother, not his father.

He says as much (“You were my brother!”) in the final scenes of Episode III, and Filoni points out that Anakin is deeply damaged by this lifelong absence.

And so, in turn, is Mando. Although he has integrated into a family structure as an adopted Mandalorian, the orphaned Mando has shut off emotional connections to other sentient beings, but Baby Yoda captures his softer emotions in a way his other quarry has not.

By going on the run with The Child, Mando abandons all that he has ever known since he himself was orphaned.

In the same way, Luke Skywalker triumphs in Return of the Jedi where he fails in The Empire Strikes Back — he has finally formed a full willingness to sacrifice, but not for himself, or his friends, or power, or even the democratic political system he wants.

I have been thinking about Star Wars for almost three decades, and now it is my job to think about Star Wars, and I have never yet truly grasped what George Lucas meant when he said that “Star Wars is for children.”

It’s… what?

Then explain the arm-chopping and the 55-year-olds at Comic-Con encased entirely in stormtrooper plastic for three solid days.

After Filoni and his co-creators provide their perspective in this episode, I now know what Lucas meant. “This is for the generation that’s coming of age.” This is how we communicate what grounds and joins us as human beings.

And in a world riven by hot social media takes and weapons of mass irony, we do it via a streaming app.

“We don’t just want an action movie,’ Filoni says at one point. “We want something that makes us feel uplifted.”

And we don’t just want something that makes us feel uplifted. We want to experience the ring of ageless truths, of assurance that by the time the credits roll, the good guys are gonna make it.

The Mandalorian is now streaming on Disney Plus.